b e g i n n i n g s

Raised in a rural town in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States, I grew up with a love of nature and exploration. Whether devising contraptions in the garage, or building forts with friends in the forest . . . a creative impetus was innate.

The Olympic and Cascade mountains, the Pacific Ocean, Puget Sound, a pan abode log cabin on Lake Cushman, and the lush woods surrounding my childhood neighborhood were the environs in which I spent my time making, playing, snow skiing, boating, hiking, and mountain biking.

Thankfully, my parents recognized my artistic, analytical, and experimental aptitudes, and suggested the profession of Industrial Design as I considered higher education options while in high school.

Upon then visiting a state university for an introduction to their industrial design program, I found my calling : building better user experiences. Avid to excel, I would soon become a fervent studyholic on campus, and then a workaholic in actual practice, avidly pursuing his potential.

Peninsula College in Port Angeles, Washington, where a philosophy professor’s life had an unexpected influence. Image | Your Future in IT

Starting with the general courses for an Associates of Arts degree at Peninsula College, the most memorable class was Philosophy 101. However, the lessons that remained came more from the history of the teacher himself than from the Classical Western thinkers about whom he taught. Professor Werner Quast was uniquely qualified for his post, which was all about rousing young minds to open up . . .

As a young, German teen during World War Two, he was involuntarily drafted into the Hitler Youth military corps and stationed at a prison camp. Hearing the captured inmates recount the Nazi atrocities across Europe, he befriended them and did what he could to bring them extra food and otherwise ease their internment.

At the close of the war, when Allied forces roared into the camp to liberate it, only by the POWs shouting through the barbed wire fence to spare him, did Mr. Quast survive that day. After then learning the dreadful reality of the war’s horrors, he was so infuriated at his country having been so heinously deceived by their government and for the public following so blindly, that he dedicated his life to teaching people to think.

What more vital message did Plato, Aristotle, or Socrates possibly have to offer than that? It was a profound thought that would inspire me to think more broadly and deeply about what people valued and why, as a means to then instill designs with the most meaningful attributes.

c r e a t i v e t r a i n i n g

Recyclable 35 mm camera concept with rear, handlebar clip for mountain biking photography.

The next step though, would be to transfer to Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington to earn my Bachelor of Science, Industrial Design degree.

Enthralled with the creative curriculum while also anticipating the prospective, employment competition ahead, I spent twelve to sixteen hours a day, six to seven days a week on related, degree studies and in the design studios.

This dedication led to a propitious, summer internship granted by Virtual Vision, a head-up display, high tech startup that had sponsored a junior year project.

Western’s ID program prepared students to comprehend the entire, product development process, with a strong orientation towards manufacturability through a practicum in materials and mass production technologies.

And on the creative side, In addition to skills in ideation, sketching, iterative mock ups, CAD drawing, and presentation, students were also trained to imbue products with meaning and value for end users by combining required function and attractive form expressed through intuitive features and personally relevant, subconscious insinuation.

The functional, camera prototype demonstrated knowledge of materials and methods for mass production.

The camera also made a cameo appearance in an article by frog design published in Graphis 298 magazine, Vol. 51.

We not only made physical models, but also built working prototypes of our senior projects, including a polished aluminum warming trivet to serve heated desserts after a romantic dinner for two, a recyclable, 35 mm film camera for mountain biking treks, and a reconfigurable, room divider screen with enticing character to inhabit a postmodern, residential decor.

Graduating as WWU’s annual, Industrial Design Society of America, Student Chapter Merit Award recipient, I’d learned that there was more to product design than outward appearance alone.

Trusting too, that there was much more to learn within the industry itself, I headed south on Interstate 5, to look for a vocation where I longed to vacation . . . California.

i n i t i a t o r y c a r e e r

As a recent grad, my first professional opportunity was in the East Bay of San Francisco, with Compass Product Design led by Curt Anderson, formerly of Xerox Corporation. I was his first hire as his prior partnership transitioned into a consultancy.

I was immediately partaking in all areas of development, including mechanical engineering, tooling documentation of molded plastic and sheet metal parts, and building visual models and fully functional, trade show prototypes.

This level of participation brought direct interactions with clients and vendors, and a spectrum of experience across medical, consumer, and office product categories. I was grateful to learn so much in such a short amount of time.

Multifunction office printer | scanner | fax machine designed for JetFax Inc. as an entry level designer with Compass Product Design.

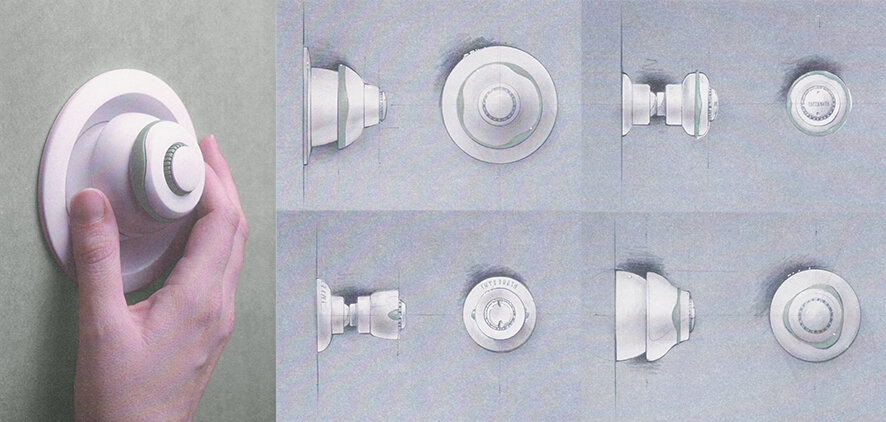

Articulating model and concept sketches of a body spray shower system for Interbath while at Hauser Inc.

I moved on to join the national, top ten consultancy, Hauser Inc. in Thousand Oaks near Los Angeles, California, where I worked with exceptionally talented people from whom I gained a greater sense of creativity and appreciation for design detail.

Involvement with more sophisticated, ethnographic, market and user research steadily increased my awareness of why I was designing, beyond simply what I was designing.

This growing interest then drove a dedicated search for a deeper understanding of people, including myself, that would in turn drive better product design.

At the same time, I realized my part in the mass consumption cycles driven by companies pushing for ever more rapid refresh rates to sell new products. So, sustainable product development became another area of interest.

After Hauser, then, it was back to Seattle to begin my own, environmentally friendly furniture company, known as LUMA, designing and building hand crafted furnishings of wood, aluminum, fabric, glass, and stone. The pieces came about through a careful and experiential consideration of their function, taking on forms connoting a casual, sensible life balance.

Along with the freedom of expression that LUMA afforded, it was also a wonderful way to learn about balancing the business aspects of design, and also to enliven and embolden fresh, personal views.

As an amateur anthropologist, the ongoing studies of American and other countries’ customs and beliefs intertwined philosophy, psychology, physiology and health, history, religion, economies, and politics.

It was a deep dive into the existential alchemy of humanity itself. What were the patterns in our commonalities, despite such variant means of attaining our needs? What motivated us, from continent to continent, individually and communally? What basis did we have to believe in the ways espoused by our societies? And, how could we improve?

Traversing ancient, aboriginal traditions, East Asian principles for unity with nature’s unseen forces, and eclectic, New Age modes of thought, the explorations constituted a renaissance of sorts.

And, while constructive as an era of personal development, the methodology was confined to a domestic context rather than conducted through in situ observation . . . a limitation to correct in the next phase of learning ahead.

LUMA, Selinn sofa table of maple and aluminum with storage for periodicals.

Journal sketch of Senhora Da Peneda church, Portugal.

t r a n s f o r m a t i v e t r a v e l s

In early 1999, the continuing curiosity about cultures eventually swayed me to leave LUMA behind and pursue international travels for more direct learnings about other ways of life.

The first six months unfolded across Europe, backpacking through about a dozen countries where epic, Western history came into clearer view, as did a contrasting vantage on modern America as a revealing, personal mirror.

In conjunction with the evident consumerism I knew, the prevalence of nationalism and individualism would surface as integral elements of America’s cultural profile too. Whereas, Europeans exhibited a greater sense of international awareness and cooperation.

For the few months thereafter, I lived in view of the medieval, Castle of Leiria, Portugal, working with the consultancy, grandesign, led by the charismatic, José Manuel dos Santos.

Projects ranged from a faucet exhibition installation and residential recycling concepts, to an ambitious, wireless, hand held transaction device for digital commerce on the move—seven and ten respective years prior to the iPhone and iPad.

Overall, Portugal taught a relaxed, work life balance, with an emphasis on life. And, as for work, the nation’s craft heritage of intricate stone carving, painted ceramic wares, and hand blown glass was captivating.

The next ten months were then spent in Turkey, including a month touring Syria and Jordan, which, taken together, proved to be the most fascinating and influential.

In Istanbul, the European vestiges of Greco Roman civilization and ornately spired, Gothic cathedrals of Christian antiquity gave way to the splendorous, Ottoman Empire architecture of flowing domes, slender, cylindrical minarets, and landscaped, courtyard fountains walled with open, arched arcades. With further discoveries and discussions throughout the country and through the seasons, a window into a another world would appear.

The region’s public expressions of faith, such as daily prayers and the Ramadan month of fasting, illustrated a devotional—rather than political, commercial, individual—paradigm for relative, cultural cohesion, consumer restraint, and personal confidence. Their traditional, societal narrative linked a well preserved, cosmological past and a present life of personal responsibility, with a communal certitude in an infinite future.

As one gesture typifying Turkish virtues, a pair of young men I met at a restaurant offered me residency in their meager, Sultan Ahmet flat for free, indefinitely. Graciously accepting for the first couple of winter months, I would then move to the upscale, faculty housing of Istanbul Technical University upon becoming a Visiting Instructor of industrial design there.

Visiting several survivors of Turkey’s prior August earthquake—families still living in emergency shelters months later—attested to the population’s resolute patience and hope to overcome catastrophe.

In the summer of 2000, then, Syria and Jordan’s ancient desert sites, shared holy lands, and thriving, millennium old cities, such as Petra, Mount Nebo, and Damascus respectively, would offer an Arab picture of human tenacity and tribal bonds amid life’s trials. Their social support structure was built upon family relations and reliable friends, rather than imposing a stoic independence or a dependency on government assistance.

Witnessing their scarce resources, the rugged geography, and clenching, arid climate, the people’s consistently selfless acts within the humbleness of their lives contributed most to my journal note that, “those who have the least . . . often give the most”.

Complementing Turkish and Arab generosity, other mores conveyed their reverent grasp of human nature too. The elderly were highly regarded for their life’s work, wisdom, and for generally requiring greater care. Motherhood and women’s modesty honored the sacred basis of stable families as inherently essential for the well being of society. And a person’s privacy and reputation were also respected as inalienable human rights.

Although initially appearing conservative from a foreigner’s view, I could sense, and see, the sublime wisdom in the tenets over time too.

A masjid courtyard and ablution fountain, Istanbul, Turkey.

A Bedouin boy sends flute songs towards the Dead Sea from the cliffs beyond Petra’s Monastery. Can we learn from those who live simpler lives at a slower pace to save us from destruction by over consumption?

Traveling was naturally a period of reflection, as a personal quest for experiential knowledge of human values, and of my own values. Among the diversity, I wondered if there was a common motif underlying it all, through which we could face challenges more effectively as a collective whole, just as a bundle of reeds is stronger than the same number separately.

I would find that culture, climates and conditions, foods and fashions, art and architecture all changed from place to place. But peoples’ fundamental desires remained similar—control of their lives, a sense of belonging, and optimism towards life ahead.

It was the variety of the various approaches to fulfilling these desires that proved most edifying in relating products to people and in revising my own perspectives more inclusively.

By being outside the artifices of my native, societal constructs, I was able to recognize how strongly one's surroundings shape their world view. And able to realize our potential to reposition those outlooks for the better if we look through a larger lens and release the attachments that hold us back.

History, customs, education, economics, politics, geography, resources, commerce, and religion or a lack thereof, all combine to form a projected measure of success. It seems we maneuver our lives by these measures, directing our choices in people, places, professions, piety, and of course—products.

It is through these means that we then strive to satisfy our needs for control, belonging, and hope. All desires to be addressed and refined in part through design, including how one designs their own self.

e x p a n d i n g a s p i r a t i o n s

Returning to the States in late 2000 with a new priority on family, and filled with promise to have more influence for a greater good, I joined the environmentally recognized, Watson Furniture Group near Seattle, Washington, to form and lead an internal design team.

As Director of Product Development, the initial role was to guide the creation of a pioneering line of office furniture in just six months—fusing a European feel with domestic client desires, to enter the higher tier, architecture and interior design market.

Also foreseeing further potential, and having a design consultancy background, I directed the development of Watson’s first, proprietary digital device—an innovative, comfort control system for public safety, call center operators.

Watson represented a tremendous chance and a welcomed challenge to apply my professional skills with an impactful purpose, inspired by its leadership, gaining interpersonal and interdepartmental management skills, learning to capably handle contingencies, and seeing the success thereof.

A Watson, Fusion Desking 120° workspace layout enabling impromptu reconfiguration.

Intel mobile device concept inspired by regional woodcraft geometry, for the Middle East, emerging market.

A position with Intel corporation near Portland, Oregon, then brought the next, evolutionary career step, creating and leading on a larger scale. In senior designer and project manager roles, I worked with the User Center Design (UCD) group to develop futuristic product prototypes that informed Intel’s strategic, technology roadmap—without producing any actual products, which again appeased my ecological principles.

As a project manager, it was an occasion to lead a diverse team of about 35 members spanning several disciplines and geographies, in partnership with an even larger program and internal department.

My past also enabled distinct contributions as a senior industrial designer, to develop mobile products not only for potential, mass markets world wide, but also for the emerging, Middle East market in particular, having culturally specific attributes to address within discrete, demographic sectors.

Intel offered insights into the dynamics of a corporate world with vast extents. I saw, though, that in any organization, the core ingredient [tech pun intended] for progress in design or operations is effective relations—an ability to understand people and offer solutions based on their mutual interests.

When Intel later chose to defund the UCD group, and having connections in the Near East, in 2009 we resettled in Amman, Jordan, where I would become Director of Institute Development for Qasid Arabic Institute.

As a plunge into primarily service interactions and online interaction design, the new focus built upon my work with UX and UI designers from material products, while promoting a more nuanced notion of user experience in the virtual domain.

Internet apps and cloud based technologies became a new medium to correlate students, staff, administrative information, enrollment communications, and digital instructional content, and also to deliver an intensive, comprehensive, study abroad, cultural immersion education.

These skillsets were then a means to develop the hospitality interactions, information management, logistics, and accommodation facilities of the institute’s housing program.

To serve about 400 annual residents, these offerings ranged in scope from conventional, apartment bookings for individual students, to partner group packages, and home stay arrangements with local host families.

An intuitive grasp of foreign user concerns and expectations relative to domestic, regional conditions, along with apt knowledge of local customs, would bring about the program’s overall success.

Qasid, and life in Amman, defined new technical skills while introducing the service sector and imparting the essential qualities of servant leadership.